RUSSIA’S COLLECTION OF RARE MAORI ARTEFACTS THE SECOND LARGEST IN THE WORLD

by Thomas S.

Tales of Antarctic exploration are some of the most riveting stories of adventure, especially given that early expeditions were often venturing into what were essentially unknown realms at the time. The first Russian expedition of this nature took place between the years 1819- 1821, with the aim of disproving the existence of a suspected seventh continent, or ‘Terra Australis’ in the deep south.

Two sailing ships, the Vostok commanded by Fabian Bellingshausen and the Mirny commanded by Mikhail Lazarev, departed Russia on 4th July 1819. Meanwhile, a parallel expedition was also conducted at the same time, with the Otkrytie and the Blagonamerennyi dispatched to discover a passage from the Bering Strait to the Atlantic Ocean.

To many at the time, the existence of a large southern landmass was a logical assumption, in order to balance the Eurasian continent, lest the spherical conception of the earth topple over itself. Given the scientific nature of the voyage, Ivan Mikhailovich Somonov, an associate professor of the Imperial Kazan University, as well as a painter by the name of Pavel Mikhailov, accompanied the crew.

During preparations for the expedition, instructions were published by the Ministry of Sea Forces and signed by Tsar Alexander I, the Russian Emperor of the time. Amongst the objectives set out in the document, was an important caveat for those embarking on the scientific expedition.

According to the document:

“The Emperor also commands that in all the lands which they will approach, and in which the inhabitants live, to treat them [locals] with the greatest affection and humanity, avoiding as much as possible all cases of causing offenses or displeasure, but on the contrary, trying to attract them with caress, and never apply too strict measures, unless in necessary cases, when the salvation of the people entrusted to his superiors will depend on this.”

In other words, the expedition was intended as a scientific enterprise, without the usual political ambitions for conquest and imperial expansion which were common amongst world powers at the time.

CAPTAIN COOK’S INFLUENCE:

Formerly, British naval officer Captain James Cook had been the first navigator to cross the Antarctic Circle during his second navigation. Impenetrable sea ice however, prevented him from venturing far enough to prove or disprove the existence of Antarctica during attempts made in January of 1773 and 1774.

According to Cook:

“The risk associated with sailing to these undiscovered and under-researched and covered with ice seas in search of the Southern continent is so large that I can bravely claim that not a single person will reach South further than I was able to do. Southern lands will never be researched.”

It has been suggested that Jean Baptiste Traversay, who was serving as Minister of the Russian Sea Forces at the time of the expedition, had wanted to outperform Cook’s previous exploration of the south. Traversay had previously fought the British as a French naval officer in support of the Americans during their war for independence, and later was invited to defect and join the Russians in the aftermath of the bloody French revolution.

Despite the perils to be found at the end of the world, the expedition was ultimately successful and the adventurers sailed within 13-15 kilometres of the Antarctic landmass, charting navigational features along the way.

Having survived the deep south, the ships then rested in Port Jackson, Sydney, during their first visit to Australia, where repairs were made and the crew rejuvenated themselves. After leaving Port Jackson and prior to exploring the warmer climes of the Pacific Islands, the ships were forced to seek shelter after encountering bad weather off the coast of New Zealand.

The Russian explorers had naturally made use of Cook’s charts and navigational records during their voyage, and made haste toward the safety of Queen Charlotte Sound, the Easternmost part of the Marlborough Sounds at the top of the South Island.

Interestingly, the Marlborough Sounds are also home to the shipwreck of the Mikhail Lermontov, a Soviet-era Russian cruise ship which sunk in 1986 after cutting open her hull in shallow waters.

While anchoring off Ships Cove, the Russian ships were approached by two waka (canoes), which included an older gentleman, assumed to be of chiefly status, who was welcomed aboard the Vostok and who met with Bellingshausen.

Among the copies of Cook’s records accompanying the explorers was a list of Maori words which had been acquired by Cook. Making use of this, Bellingshausen was able to communicate the desire to trade for food, such as fish.

TRADE & HOSPITALITY:

After establishing trust with the rangatira (chief) aboard the Vostok, the Russians then entered into a warm exchange of trade and hospitality with the locals who had come to greet them. Fortunately, the expedition had procured a supply of tradable items for such an occasion, including knives, mirrors, saws, axes, scissors, needles, nails, wax candles, chisels, rasps, files, kaleidoscopes, beads, fabric, combs, wire, buttons and so forth.

In exchange for these items, which were of high-value to the natives, the Russians obtained a range of artefacts of cultural and anthropological significance, including pounamu (greenstone), various weapons, kākahu (cloaks), wakahuia (treasure boxes) and even preserved heads, which were often taken as war trophies.

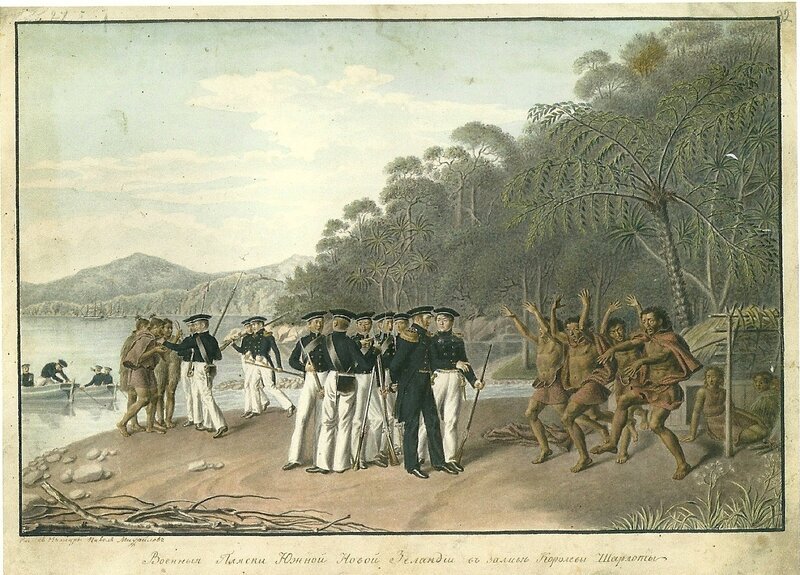

During the exchange of hospitality and commerce, the expedition’s artist also made various sketches, wherein characteristics unique to the local people, such as traditional tattoo patterns, hairstyles, clothing, carvings and so forth, were captured for posterity. Several lines of haka were also recorded by the crew.

These records are significant compared to Cook’s, because Cook met with various peoples and may not have made distinctions on finer details observed amongst different tribes, whereas the Russians only met with one people and preserved an account of their distinct cultural idiosyncrasies.

The items collected were eventually distributed between the Kunstkamera Museum in St Petersburg and the Kazan Federal University, after the expedition’s return to Russia, although several items appear to have been lost along the way.

The collection today is the second-largest collection of rare Maori artefacts, save only that which was obtained by Captain James Cook. The collection, which holds immense significance for both the Russians, as well as Maori, has only grown in value over time.

After all, just eight years after the Russian explorers departed, an ally of the North Island warlord Te Rauparaha, killed and enslaved the majority of the peoples settled in the region, with a number of survivors fleeing the massacre.

It is the descendants of these survivors who now look to the Russian collection as the only remaining record of their ancestors’ heritage, which like other tribes, was unique among the various peoples of pre-colonial New Zealand.

Unlike artefacts obtained through conquest or exploitation, the Bellingshausen-Lazarev collection was traded for legitimately by a non-colonial power in good faith. As such, the artefacts rightly belong to the Russian people.

However, given the special interest involved, the artefacts (or taonga) are an opportunity for New Zealand to re-establish cross-cultural relations with Russia, with the potential for experts to advise on cultural and curatorial matters. Not only that, but this would also open possibilities for ‘virtual repatriation’, or the electronic cataloguing of these artefacts in a locally-available database.

The New Zealand government’s ongoing hostilities however, by way of extreme economic and political sanctions against the Russian Federation, as well as ongoing military support to the illegitimate Kiev regime, are barriers to establishing dialogue over these artefacts.

Everyday New Zealanders, however, such as the descendants of the Kurahaupō iwi such as Ngāti Kuia, Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō and Rangitāne o Wairau, whose ancestors were those who traded with the Russian expedition two centuries ago, still have the opportunity to establish cultural relations with Russia, independently of the New Zealand government.

Earlier this year, for instance, Counterspin Media attended the Second Congress of the International Russophile Movement in Moscow, where hundreds of delegates from more than 130 countries around the world were gathered for an exchange of culture and good faith.

The same will be held again next year, and there is no reason why international delegates should not be treated to a traditional pōwhiri from the descendants of the survivors of those who traded with the Bellingshausen-Lazarev expedition, which is well known by the Russian people.

Whether or not this happens, is up to the people of New Zealand, not our corrupt and belligerent government, to decide.

-

-

Tuesday - July 30, 2024 - New Zealand

(125) - NZ Government

(86) - Politics

(75) - Spiritual Warfare

(49) - Uncategorized

(42)

Leave a Comment