Provincialisation: The Answer To New Zealand’s Discontent?

by Vince McLeod

This essay outlines a suggestion not heard for many years: that the political needs and wants of the New Zealand nation could best be met by devolving political power to provincial governments.

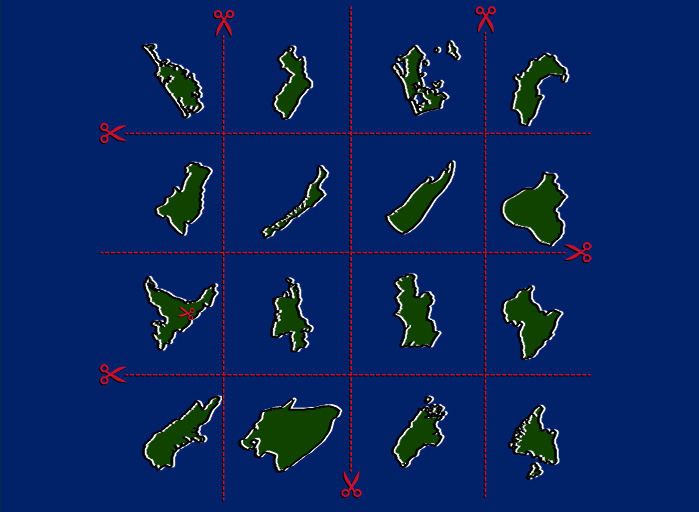

Recent demographic work has revealed the full extent of New Zealand’s demographic diversity. New Zealand is actually a fairly large country, measured by land area: it’s larger than the United Kingdom, twice as large as Bangladesh and close to three times the size of South Korea. This is spacious enough for more diversity than one might predict from a small population.

Already it’s hard enough for the entire nation to agree on anything. The country is almost evenly split when it comes to support of the left-wing bloc vs. the right-wing bloc. No matter who wins the election this October, close to half of the country will be disappointed with the result. For all of the 35 years I have followed politics, whoever was not in power was always whinging about that fact.

On many other issues we are far from unified. The cannabis referendum was also an almost even split, with 48.4% of the population losing the potential freedom to use cannabis. When it was found that wage-earners voted in favour of the measure and pensioners did not and that people were more likely to vote for change the better educated they were, the result was a bitter pill for many.

The discontent created by such outcomes recalls a 19th Century solution that might once again be of use to us: breaking New Zealand up into provinces. That way, each individual province could pass the laws that best fit the wishes of their respective populations.

New Zealand had a provincial government up until 1875, when it was abolished by Julius Vogel, perhaps out of globalist considerations. Ever since then, New Zealand has suffered under one of the most centralised power structures outside of actual dictatorships. Re-establishing the provincial government, and decentralising power back to the regions, could reduce discontent and resentment by giving Kiwis more say in their everyday affairs.

Auckland could become a city-state province with very few trade restrictions, befitting its position as New Zealand’s major trading centre. They might also like to have a Dubai/Qatar/Singapore-style slave army of cheap labour imported from South Asia, which would not be tolerated in many of the other provinces.

Wellington could become a federal capital like the ACT in Australia, or Washington DC in America, in which representatives of the provinces would meet to pass federal laws. It may or may not also have a government just for Wellington Province. This would ensure there was a minimum of disruption for Wellington and for the remaining central government in the transition to decentralisation.

Tuhoe, who have always claimed independence on the grounds that they did not sign the Treaty of Waitangi, could become a self-governing province. They would only be subject to federal law, and would otherwise have the freedom to set their own cultural agenda.

Nelson and Westland provinces could legalise cannabis and grow it on a wide scale, as well as legalise cannabis cafes that serviced both the local and the tourist markets. There’s no reason why these provinces need to have cannabis prohibition just because Pacific Island and Chinese immigrants in Auckland voted for it.

The South Island provinces could collectively reject the grievance industry around Maori land which has engulfed North Island politics, and national politics by extension. Since all the confiscations were made in the North Island, the South Island provinces could reject the “stolen land” narrative and, like Tuhoe, set their own cultural agenda.

When it came to issues like vaccine mandates, individual provinces might wish to have their own policies. The young and healthy population of Auckland Central (Auckland itself might break down into several provinces) might argue that they don’t need compulsory vaccination, whereas the elderly populations of Canterbury and Hawke’s Bay might decide otherwise.

There would still be a central government whose jurisdiction was defence, diplomacy, trade, immigration etc. This would still be known as ‘The New Zealand Government’. It follows that there would still be an All Blacks, a New Zealand Symphony Orchestra etc. but more focus and funding would be directed to the next level down.

With this model, if a person found the laws of their province intolerable, they would be free to move to another province that suited them better. If the high taxes of Canterbury and Otago didn’t suit, a person would be free to move to Auckland. Likewise, if the lowsocial investment, high-crime model of Auckland didn’t suit, a person would be free to move to Canterbury and Otago.

All moral issues would be decided by provincial governments: abortion, gambling, prostitution, drugs etc. This would minimise the extent to which New Zealanders had someone else’s morality forced on them (of course, for some people, forcing their morality on others is the whole point. The influence of these control freaks would be minimised under a provincialised system).

This would also mean that any one province that developed a superior political system to another would be rewarded with greater internal migration and investment. Thus, the politicians of the country would be set to competition with each other, unlike today’s arrangement, in which the politicians set New Zealand workers to competition with foreign imports.

Find this article on substack.

For more of VJM’s ideas, see his work on other platforms! https://linktr.ee/vjmpublishing

-

-

Friday - June 16, 2023 - Culture Wars

(69) - New Zealand

(122) - NZ Government

(84) - NZ Investigation

(28)

Leave a Comment